My Last Duchess by Robert Browning

Check out another good one here.

My Last Duchess

That's my last Duchess painted on the wall,

Looking as if she were alive. I call

That piece a wonder, now: Frà Pandolf's hands

Worked busily a day, and there she stands.

Will't please you sit and look at her? I said

"Frà Pandolf" by design, for never read

Strangers like you that pictured countenance,

The depth and passion of its earnest glance,

But to myself they turned (since none puts by

The curtain I have drawn for you, but I)

And seemed as they would ask me, if they durst,

How such a glance came there; so, not the first

Are you to turn and ask thus. Sir, 'twas not

Her husband's presence only, called that spot

Of joy into the Duchess' cheek: perhaps

Frà Pandolf chanced to say "Her mantle laps

Over my Lady's wrist too much," or "Paint

Must never hope to reproduce the faint

Half-flush that dies along her throat": such stuff

Was courtesy, she thought, and cause enough

For calling up that spot of joy. She had

A heart — how shall I say? — too soon made glad,

Too easily impressed; she liked whate'er

She looked on, and her looks went everywhere.

Sir, 'twas all one! My favour at her breast,

The dropping of the daylight in the West,

The bough of cherries some officious fool

Broke in the orchard for her, the white mule

She rode with round the terrace — all and each

Would draw from her alike the approving speech,

Or blush, at least. She thanked men, — good! but thanked

Somehow — I know not how — as if she ranked

My gift of a nine-hundred-years-old name

With anybody's gift. Who'd stoop to blame

This sort of trifling? Even had you skill

In speech — (which I have not) — to make your will

Quite clear to such an one, and say, "Just this

Or that in you disgusts me; here you miss,

Or there exceed the mark" — and if she let

Herself be lessoned so, nor plainly set

Her wits to yours, forsooth, and made excuse,

--E'en then would be some stooping, and I choose

Never to stoop. Oh sir, she smiled, no doubt,

Whene'er I passed her; but who passed without

Much the same smile? This grew; I gave commands;

Then all smiles stopped together. There she stands

As if alive. Will't please you rise? We'll meet

The company below, then. I repeat,

The Count your master's known munificence

Is ample warrant that no just pretence

Of mine for dowry will be disallowed;

Though his fair daughter's self, as I avowed

At starting, is my object. Nay, we'll go

Together down, sir. Notice Neptune, though,

Taming a sea-horse, thought a rarity,

Which Claus of Innsbruck cast in bronze for me.

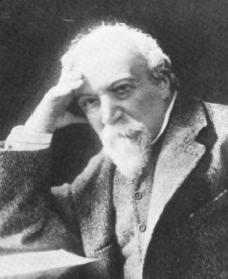

Robert Browning was born on May 7, 1812, in Camberwell, England. His mother was an accomplished pianist and a devout evangelical Christian. His father was a bank clerk and collector of rare books. After reading Elizabeth Barrett's Poems (1844) and corresponding with her for a few months, Browning met her in 1845. They were married in 1846, against the wishes of Barrett's father. He died in 1889.

Robert Browning was born on May 7, 1812, in Camberwell, England. His mother was an accomplished pianist and a devout evangelical Christian. His father was a bank clerk and collector of rare books. After reading Elizabeth Barrett's Poems (1844) and corresponding with her for a few months, Browning met her in 1845. They were married in 1846, against the wishes of Barrett's father. He died in 1889.