Chicago by Carl Sandburg

Baker of deep dish pizzas,

Loser of many baseball games,

Shuffler to the Super Bowl.

Ok, not really. Sandburg's "Chicago" is a lot fiercer than I remembered. A little disturbing, even. A good example of how poetry can be "tough." (stop snickering)

Chicago

Hog Butcher for the World,

Tool maker, Stacker of Wheat,

Player with Railroads and the Nation's Freight Handler;

Stormy, husky, brawling,

City of the Big Shoulders:

They tell me you are wicked and I believe them, for I have seen your

painted women under the gas lamps luring the farm boys.

And they tell me you are crooked and I answer: yes, it is true I have seen

the gunman kill and go free to kill again.

And they tell me you are brutal and my reply is: On the faces of women

and children I have seen the marks of wanton hunger.

And having answered so I turn once more to those who sneer at this my

city, and I give them back the sneer and say to them:

Come and show me another city with lifted head singing so proud to be

alive and coarse and strong and cunning.

Flinging magnetic curses amid the toil of piling job on job, here is a tall

bold slugger set vivid against the little soft cities;

Fierce as a dog with tongue lapping for action, cunning as a savage pitted

against the wilderness,

Bareheaded,

Shoveling,

Wrecking,

Planning,

Building, breaking, rebuilding,

Under the smoke, dust all over his mouth, laughing with white teeth,

Under the terrible burden of destiny laughing as a young man laughs,

Laughing even as an ignorant fighter laughs who has never lost a battle,

Bragging and laughing that under his wrist is the pulse, and under his ribs the heart of the people,

Laughing!

Laughing the stormy, husky, brawling laughter of Youth, half-naked,

Sweating, proud to be Hog Butcher, Tool Maker, Stacker of Wheat,

Player with Railroads and Freight Handler to the Nation.

The Sandburgs were very poor; Carl left school at the age of thirteen to work odd jobs, from laying bricks to dishwashing, to help support his family. At seventeen, he traveled west to Kansas as a hobo. He then served eight months in Puerto Rico during the Spanish-American war. He wrote many celebrated books and won two Pulitzer Prizes. Carl Sandburg died in 1967.

The Sandburgs were very poor; Carl left school at the age of thirteen to work odd jobs, from laying bricks to dishwashing, to help support his family. At seventeen, he traveled west to Kansas as a hobo. He then served eight months in Puerto Rico during the Spanish-American war. He wrote many celebrated books and won two Pulitzer Prizes. Carl Sandburg died in 1967.

Loser of many baseball games,

Shuffler to the Super Bowl.

Ok, not really. Sandburg's "Chicago" is a lot fiercer than I remembered. A little disturbing, even. A good example of how poetry can be "tough." (stop snickering)

Chicago

Hog Butcher for the World,

Tool maker, Stacker of Wheat,

Player with Railroads and the Nation's Freight Handler;

Stormy, husky, brawling,

City of the Big Shoulders:

They tell me you are wicked and I believe them, for I have seen your

painted women under the gas lamps luring the farm boys.

And they tell me you are crooked and I answer: yes, it is true I have seen

the gunman kill and go free to kill again.

And they tell me you are brutal and my reply is: On the faces of women

and children I have seen the marks of wanton hunger.

And having answered so I turn once more to those who sneer at this my

city, and I give them back the sneer and say to them:

Come and show me another city with lifted head singing so proud to be

alive and coarse and strong and cunning.

Flinging magnetic curses amid the toil of piling job on job, here is a tall

bold slugger set vivid against the little soft cities;

Fierce as a dog with tongue lapping for action, cunning as a savage pitted

against the wilderness,

Bareheaded,

Shoveling,

Wrecking,

Planning,

Building, breaking, rebuilding,

Under the smoke, dust all over his mouth, laughing with white teeth,

Under the terrible burden of destiny laughing as a young man laughs,

Laughing even as an ignorant fighter laughs who has never lost a battle,

Bragging and laughing that under his wrist is the pulse, and under his ribs the heart of the people,

Laughing!

Laughing the stormy, husky, brawling laughter of Youth, half-naked,

Sweating, proud to be Hog Butcher, Tool Maker, Stacker of Wheat,

Player with Railroads and Freight Handler to the Nation.

The Sandburgs were very poor; Carl left school at the age of thirteen to work odd jobs, from laying bricks to dishwashing, to help support his family. At seventeen, he traveled west to Kansas as a hobo. He then served eight months in Puerto Rico during the Spanish-American war. He wrote many celebrated books and won two Pulitzer Prizes. Carl Sandburg died in 1967.

The Sandburgs were very poor; Carl left school at the age of thirteen to work odd jobs, from laying bricks to dishwashing, to help support his family. At seventeen, he traveled west to Kansas as a hobo. He then served eight months in Puerto Rico during the Spanish-American war. He wrote many celebrated books and won two Pulitzer Prizes. Carl Sandburg died in 1967.

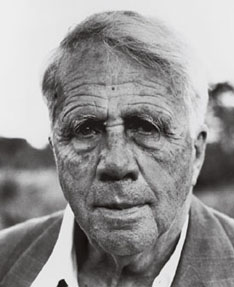

Robert Frost

Robert Frost